From Fracturing to Treatment: Decoding the Complexity of Shale Oil Wastewater

Shale Oil Wastewater: A Complex Challenge at the Crossroads of Energy and Environment

In today's world where energy demand continues to rise, shale oil hidden deep within shale formations has become an important supplementary energy source. However, what is less known is that for every ton of shale oil extracted, several times more extraction wastewater than crude oil is produced. Compared with traditional oilfield wastewater, shale oil extraction wastewater is considered by the industry as the "tough bone" in the water treatment field. What makes it special? Why has the difficulty of treatment greatly increased? Behind this lies a complex game between energy extraction and environmental protection.

How Shale Oil Wastewater Differs from Conventional Oilfield Wastewater

To understand the challenges of treating shale oil extraction wastewater, one must first grasp its core differences from ordinary oilfield wastewater.

In traditional oilfield operations, crude oil and formation water naturally flow to the surface together. The resulting wastewater mainly consists of crude oil, formation salts, and a small amount of suspended solids—its composition is relatively stable, and treatment goals are straightforward: remove oil and suspended solids, then adjust water quality to meet reinjection or discharge standards.

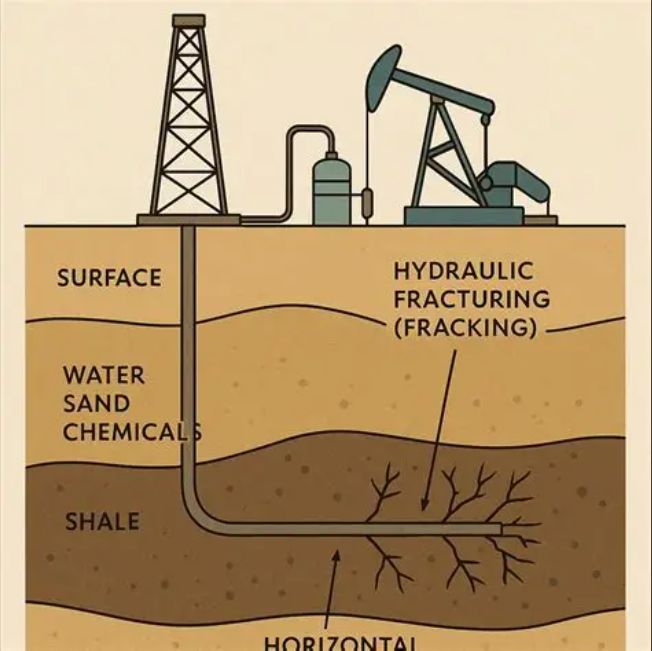

By contrast, shale oil extraction relies entirely on hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”). High-pressure water laced with chemical additives is injected into underground shale layers to forcibly fracture the rock and release trapped oil. This process creates wastewater with an exceptionally complex makeup—a double burden of artificially introduced pollutants and naturally occurring formation contaminants.

The wastewater contains dozens of chemical additives used during fracturing—such as friction reducers, breakers, and biocides—many of which include high-molecular-weight polymers that increase viscosity. It also carries extremely high salinity (total dissolved solids, or TDS, often exceeding 100,000 mg/L—more than three times that of seawater), heavy metals like barium and strontium, trace radioactive elements, residual crude oil, and proppant sand. Together, these components form a chaotic, interactive mixture that fundamentally underpins its reputation as “difficult-to-treat” wastewater.

Three Core Technical Challenges in Treating Shale Oil Wastewater

1. Co-Pollution by High Salinity and Refractory Organics

Conventional biological treatment works well for low-salinity oilfield wastewater, effectively degrading organic matter. But in shale oil wastewater, extreme salinity acts as a toxin that suppresses microbial activity, rendering biological systems useless.

Meanwhile, organic compounds like polyacrylamide from fracturing fluids are chemically stable and resist breakdown by standard oxidation or adsorption methods. Worse still, organics and salts interact to form stable emulsions that tightly bind oil and impurities in the water, making separation extremely difficult.

For example, dissolved air flotation (DAF) can remove over 90% of oil from conventional wastewater—but its efficiency plummets when applied to shale oil wastewater. Advanced oxidation pretreatment is often required first to break down large organic molecules before any meaningful separation can occur.

2. Extreme Variability in Wastewater Composition

Stable influent quality is essential for consistent treatment performance—but shale oil wastewater is notoriously inconsistent.

Early in a well's life, flowback water is dominated by unused fracturing fluid: high in chemical additives but relatively low in salinity. As production progresses, formation water increasingly mixes in, causing salinity and contaminant levels to surge unpredictably. Even between different wells or stages of operation, wastewater characteristics can vary widely.

This volatility demands treatment systems with exceptional flexibility and shock resistance. Fixed, conventional processes often fail—they’re tuned for one condition, only to face a completely different water profile days later—leading to unstable performance, regulatory violations, or soaring operational costs.

3. Scaling, Corrosion, and Equipment Degradation

Shale oil wastewater is rich in scaling ions like calcium, magnesium, and sulfate. During treatment, these readily form insoluble precipitates such as calcium carbonate and barium sulfate, which coat pipes, membranes, and evaporator surfaces—a phenomenon known as scaling.

Scaling reduces flow, lowers efficiency, and can permanently damage equipment. Compounding the problem, the high salinity and fluctuating pH create a highly corrosive environment. Standard carbon steel cannot withstand these conditions; instead, expensive corrosion-resistant alloys like titanium or Hastelloy are required—significantly raising capital costs.

Membrane-based systems are especially vulnerable: fouling from organics and scaling rapidly degrade performance, necessitating frequent cleaning or replacement and driving up operating expenses.

Emerging Solutions: Toward Zero Discharge and Resource Recovery

Despite these challenges, the industry is actively developing innovative approaches. The prevailing strategy combines staged treatment with resource recovery:

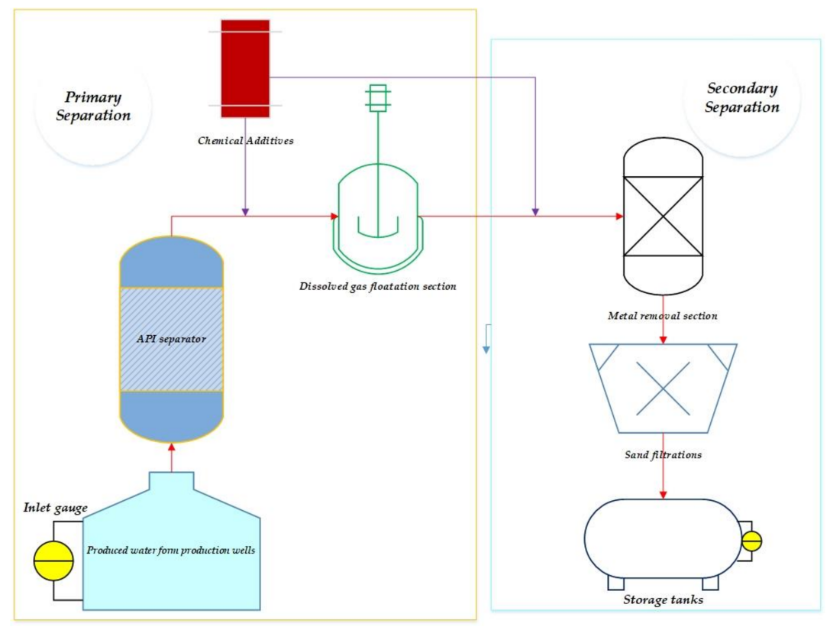

●Pretreatment: Processes like coagulation, flotation, and advanced oxidation remove suspended solids, break down refractory organics, and reduce hardness—preparing the water for downstream steps.

●Advanced Desalination: Membrane technologies such as ultrafiltration (UF) and reverse osmosis (RO) recover clean water for reuse.

●Concentrate Management: The remaining high-salinity brine undergoes mechanical vapor recompression (MVR) evaporation and crystallization, turning dissolved salts into solid industrial-grade byproducts—enabling true zero liquid discharge (ZLD).

To address logistical hurdles like remote, scattered well sites and variable water quality, modular and mobile treatment units are gaining traction. Meanwhile, smart monitoring and control systems use real-time data to dynamically adjust process parameters, enhancing reliability and efficiency.